From a refreshing beverage to a tasty delicacy, the source of a staple to material for clothing, shelter and jewellery, the Ite Palm has truly been the tree of life for the indigenous society, providing all the necessities of daily living.

Upon entering the Walter Roth Museum, just to the left of the entrance, one can find an interesting exhibition on the Ite Palm. Several items created from the by-products of the palm are displayed, coupled with the ecological and historical background of the tree in English and Portuguese respectively.

Before the Arawaks brought cassava to Guyana, the wonders of the Ite Palm were explored by the Warrau tribe. “To the Warrau, the Ite was called the ‘tree of life’ and we can see why with its benefits and the fact that just about every part of the palm can be used,” explained Guyanese archaeologist Jennifer Wishart in an interview with Sunday Times Magazine.

Sitting in the cosy gallery of the museum, surrounded by a beam of natural light, enveloped by a cool breeze, Wishart stated that the palm, scientifically called Maurita flexuosa and is generally known as the ‘Morichi’, can be found growing in moist acidic soils in the North Western regions along the coast and in the interior savannah of Guyana.

A wide variety of market and household products, as well as various environmental, ecological and economic benefits, can be derived from the tree itself. Even the by-products of the tree are also be used as a good source of protein and starch.

“The tree provided a source of starch before cassava because the Arawaks were the ones who brought the knowledge of cassava here as the Warrau were already using their Ite. That is why they are called Arawak meaning the ‘cassava root’ in Warrau,” noted Wishart.

According to Roxanne Skeete, a resident of the Barabina Village, “when the fruit is in season it is used for several purposes around the village. The drink is very tasty when chilled and the otocumba [tacuma worm] is used in tumapot (pepperpot) or is fried to be eaten with bakes or cassava bread”.

Even left to rot, the tree proves its worth. “In event the dugout tree trunks are left to rot, the Rhyncophorus palmarum beetle comes and lays eggs in the holes. These larvae that feed off the tree trunk develops into the otocumba worms, which are prepared as a great delicacy,” stated Skeete.

“The tacuma worms come from the fallen palm trees. We would dig out holes in the trunk, cover it with the leaves from the tree and let it rest for about six weeks. Within the six weeks we check it constantly. When we hear them buzzing, we take the axe burst it open and take all you can get,” Elysha, who worked at the local indigenous restaurant Tuma Sala, explained.

Traditionally, the Warrau would dig out the heart of the trunk and is usually eaten raw or cooked. This pith would later be drained through a matapi and its juice is used to make the Ite drink. When the juice settles, the remnants would also produce a powder-like substance that the Warrau use as flour to make bread and cakes. Additionally, they utilised the dugout trunks to make canoes and planks to build houses and structures.

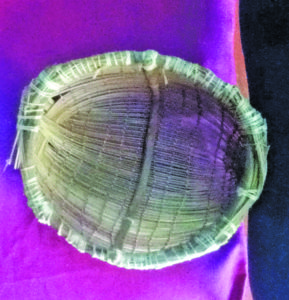

“Even the fibre of the leaves were utilised to make tibisiri, which creates intricate baskets, hammocks, furniture, carpets, thatch and warishis [haversacks],” Wishart outlined.

The shoots of the leaves could be boiled to weave clothing and the ribs used to make kite frames during the Easter season.

Today, the tradition of using the tree’s fan-shaped leaves to bake cassava bread continues to be a dominant part of the indigenous culture.

Notably, the red-brown rounded fruit of the Ite tree, usually available in the dry season, is picked and consumed as fresh fruit or dried to make oil or vegetable ivory – both economical and sustainable alternatives to otherwise expensive and environmentally hazardous products.

“The Brazilian Indians are using the seed of the Ite Palm to make vegetable ivory, a sustainable alternative to elephant ivory,” Wishart mentioned.

When dried, the seeds can be carved and dyed just like elephant ivory to make figurines, beads, buttons and jewellery. This is a tremendous ecological and environmental benefit in preventing the deaths of hundreds of elephants who are killed yearly for the ivory found in their tusks.

Unfortunately, only a few Warrau along the Venezuelan border and their families know how to extract starch from the Ite Palm, although historically it was their staple according to an excerpt from Marileen Reinders’ “Medicinal Plants and their uses and the Ideas about Illness and healing among the Warao of Guyana”.