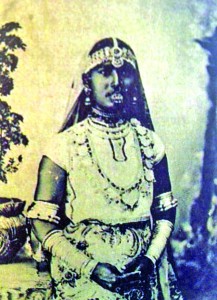

From the moment the Indians were brought into then British Guiana on May 5th 1838, they were subjected to racist discrimination and oppression. The racist assumptions that undergirded such actions were in place even before they landed. In fact, they determined their selection to replace the newly freed slaves.

The initiator of the scheme to import Indians was John Gladstone, owner of Vreed-en-hoop and several other plantations. He wrote to Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co. in India about the possibility of supplying him with “Bengalees”; he had heard they were shipping to Mauritius:

“You will probably be aware that we are very particularly situated with our Negro apprentices in the West Indies, and that it is a matter of doubt and uncertainty how far they may be induced to continue their services on the plantations after their apprenticeship expires in 1840. This to us is a subject of great moment and deep interest in the colonies of Demerara and Jamaica. We are therefore most desirous to obtain and introduce labourers from other quarters, and particularly from climates something similar in their nature.”

The reply from Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co. was revealing:

“The tribe that is found to suit best in the Mauritius is from the hills to the north of Calcutta….The Hill tribes, known by the name of Dhangurs, are looked down upon by the more cunning natives of the plains, and they are always spoken of as more akin to the monkey than the man. They have no religion, no education, and, in their present state, no wants beyond eating, drinking, and sleeping; and to procure which they are willing to labour.”

By the turn of the century, the opinion of whites about the East Indian had not improved noticeably: a newly-arrived pastor, Rev HJ Shirley, on July 1900, wrote the following in the Birmingham Post, about Indian workers on estates:

“If an overseer kicks a coolie into a trench…. the coolie has no remedy but what he takes into his own hand. Let him however strike an overseer and a batch of policemen are sent off to arrest him and he is severely sentenced to prison….there is an immigration agency which costs the country some thousands a year and is supposed to secure them justice, but supposition is not always paralleled with facts.”