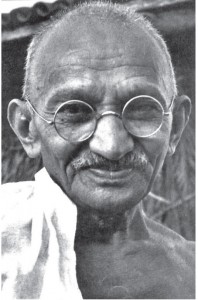

By Swami Aksharananda

October 2 marks the 144th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. This is an event that will be commemorated the world over, though in Guyana, apart from the annual event at the Promenade Gardens by the Indian Commission, little is said or done. This, however, does not mean that Gandhi is not in the news, at least the sensational side of it. In his own lifetime, he has been the centre of a great deal of controversies, and many of his views have been challenged by his own brilliant contemporaries, such as Rabindranath Tagore and Subhash Chandra Bose.

What was outstanding about the discourse he and his contemporaries had was the utter and at times brutal sincerity. Yet, he never crossed the boundary of respect and showed enormous compassion and regard for those with whom he had disagreement.

His life, as he himself claimed often, was an open book and unlike public leaders of our times, there was no demarcation between the public and private. He even slept in the open along with his disciples and co-workers.

I remember well the words of a prominent politician and activist who is now a member of parliament when some of his colleagues raised concerns about his conduct.

He declared that no one was concerned about his life behind closed doors. Not so with Gandhi! Yes, even now, we may disagree with Gandhi, but we cannot doubt the honesty and candour with which he discussed even the most intimate details of his personal life and struggles.

In reading about him, what strikes one almost like a bolt was the openness with which he talked and wrote about what he perceived as his weaknesses, particularly his sexual desires, with which he was engaged in an almost lifelong struggle.

Controversial experiment

His controversial experiments to test the strength of his powers of self-control and celibacy, or brahmacharya in traditional terms, were all done in the open.

His decision to end all sexual relationships with his wife was again discussed among his colleagues and, of course, with his wife.

In the realm of politics, Gandhi’s lasting and perpetually relevant contribution has to do with satyagraha, the pursuit of truth and the struggle against injustice.

Anyone who reads his, “Duty of Disloyalty”, cannot fail to be struck by its potency.

More than 80 years on, one experiences a sense of thrill and exhilaration. The opening salvo in this letter sets the tone for what is arguably one of the greatest documents on resistance to domination.

“There is no half-way house between active loyalty and active disloyalty.” But unlike many crusaders for justice these days, Gandhi was careful to make a distinction between persons and institutions. “You are therefore loyal or disloyal to institutions,” he wrote.

Corrupt system

Considering the state in colonial India, Gandhi concluded that it could not evoke any loyalty. It was corrupt with inhuman laws.

It was therefore the duty of those who realised the evil nature of the system to be not only disloyal to it, but “to actively and openly preach disloyalty”. He continued, “Loyalty to a state so corrupt is a sin, disloyalty a virtue.”

Further, regarding the corrupt system of government in India at the time, Gandhi stated that the, “purest man entering the system will be affected by it, and will be instrumental in propagating the evil”.

Gandhi was absolutely clear that, “a good man will resist an evil system of administration with his whole soul”. And at the same time, he continued, equally unequivocally clear and uncompromising, “Violent disobedience deals with men who can be replaced. It leaves the evil untouched and often accentuates it.”

Civil disobedience

Again, during the 1930-31 civil disobedience campaigns, Gandhi was hauled before the courts for “seditious writing”, but on this occasion, his response to the judgment singularly bold and revolutionary.

Challenging the magistrate’s right to pass judgment, he stated that the people of India owed no mare allegiance to the government of the day, “than does the man in the moon”.

And, he added with his unique style of beauty and simplicity, “Where there is no ground for a bond of affection, it naturally follows that I cannot be guilty of spreading disaffection”.

Gandhi saw that the government of India was a usurper of people’s rights and therefore its laws had “no power arising from the people in whom rests sovereignty”. He challenged the magistrate that he was an arm of the very same executive and, hence, had no jurisdiction over him, and added that it was not for him, “to participate in this farce of a judicial proceeding”.

The magistrate on this occasion was an Indian and so Gandhi concluded with a special appeal to him, “to resign the disreputable connection with a soulless machine that drinks deep of the blood of your people and descending from the throne of the usurper which you now occupy, come and stand by your own in the hour of their need”. (TO BE CONTINUED…)