By Elfrieda Bissember

Both George Simon and his brother Oswald Hussein, born in the Lokono (Arawak) village of Pakuri (St. Cuthbert’s Mission) on the Mahaica River, live with a continuing commitment to their Amerindian heritage and communities. Simon, trained in printmaking in London and a leading Guyanese painter since the late 1980’s, began workshops at this time in Pakuri to encourage and stimulate creative activity in the plastic arts among all those who were interested in these possibilities.

His brother Oswald emerged as a significant talent during this period, winning two awards: the First Prize for Sculpture from the major national art competition, the National Visual Arts Exhibition (NVAE), in 1989 and 1993; Simon himself had won the Judges’ Prize for Painting at the NVAE in 1986.

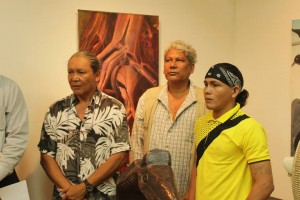

Additionally, with another promising Pakuri artist, Linus Clenkian, Simon and Hussein showed work at the National Gallery in 1995 in a landmark exhibition, ‘Contemporary Amerindian Art’, marking the World Decade of Indigenous Peoples.

What has been significant in this group over the last twenty years is their identification with the elements and features of their hinterland environment. A vibrant group show at the Venezuelan Cultural Centre in 1998, Six Lokono

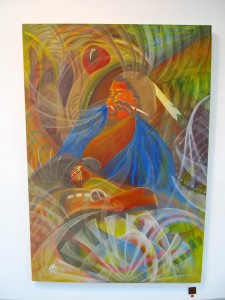

Artists, heralded them as ‘Artists for the Environment’; and their inventive and fascinating forms, so often a mixture of challenging fantasy yet grounded in and springing from the life and habits of forest fauna, and decorated with elements of its flora, have made the convincing case for their authority to express the growing concerns of the wider Guyanese community, and to symbolize the precious natural heritage of the land and its resources celebrated in their work.

Another constant factor has been the commitment to working with young, potential artists in their own and other Amerindian communities, as well as, through Simon, organizing group projects such as the design and painting of murals (the newly built Guyana National Stadium in 2007, the Umana Yana in 2008, and the School of Education and Humanities building, University of Guyana in 2010), where an students could participate in a useful exercise in skills training.

Simon and Hussein’s current co-exhibitor, Victor Captain, is such an example. A promising painter, he met Simon, a 1994 London University graduate in archaeology, at the Bina Hill Institute at Annai, North Rupununi in 2009, by which time, however, Captain had had a secure interest in art, through participation at the age of ten at a Wild Life Festival organized by the Iwokrama Rainforest Reserve, and later through the teaching of young Makushi artist Anil Roberts, a Burrowes School of Art and University of Guyana graduate and a protégé of Simon’s, who taught at Captain’s school in 2005-6.

Why ‘Silent Witness’? Nature in fact forms the base for these artists’ inspiration, but also we are to be reminded, as here, of their inherited lore of stories, myths, legends and spiritual beliefs, which in their details are bound up with and illustrated by the myriad elements and qualities of these manifestations of nature. Further, by their instinctual and deep knowledge of the natural world, lived with and bound to at close quarters for everyday and long-term survival, physical, material and spiritual, their images spring from this intimate and authoritative familiarity and respect for the life-sustaining eco-systems which so many others are completely unaware of or do not recognize.

The works in this exhibition can therefore remind us of some of the hidden and obvious treasures that lie within the patrimony of the natural world and varied landscapes of Guyana. Nature, indeed, through the land and its various forms of thriving life, delineates those parts of the earth that we call our homeland. It is witness, and proof, of the richness and the health of this patrimony, and can indicate, by the extensiveness and vitality of its forms, how well we are managing, or sustaining, this valuable life force.

Though silent of words, the elegant, twisting forms of George Simon’s “Tree Root #1” and “Tree Root #2” speak and symbolize conditions of life; his leaping “Bimichi” (Hummingbird) revered in myth as a powerful bird, used as a charm and an embodiment of a god, is familiar yet magical creature with its glowing colour and furiously reverberating wings and body: one of the thousands of miraculous manifestations of the natural world. Simon’s “Jaguar” similarly, one of a series of recent paintings, is a dominant creature in Amerindian life and myth, symbolizing strength and protection for hunters, as well as a powerful ally of the “Shaman” (medicine man or healer) in his work; interesting comparisons are Captain’s “Guardian” and his “Hunter”, who walks with his long blowpipe above his head, slung with receptacles for poison and poison darts, and an oval of entrapping nets, stalked by the gaping-jawed jaguar providing protection and strength.

Myths and beliefs entwined with the natural world abound, as do celebrations in depiction of animal life and village pastimes. Captain’s “Banjo Man”, a Makushi-named tiny river fish, is monumentally depicted by the artist; his “Monkey Brush” is another nick named story about plant and animal life, describing a forest vine whose buds sprout curving tendrils which monkeys pick and scratch themselves with, with splits in the buds or pods also bearing flowers which spin off in the wind. His “Full Moon” shows Makonaima (God) watching over his people; his “Quara” (the Makushi word for horse) is painted in undulating, curving lines echoed by an aura of similar pattern; the macaws in “Cacique Crown” provide the feathers for this crown. And “Sun God” tells the story of the Chief who could only procreate with his wife in darkness, so sending his men to seek some hours of night from the Sun God, who guarded it in the form of an egg, giving it to them with the warning that any harm of their cargo would lose them control of the night. The egg being dropped and causing twelve hours of darkness every night, the chief’s wife was happy to pick flowers during the day, using their colours to create the animals and birds of the forest.

Finally, Oswald Hussein extracts his striking forms and mysterious shapes from the range of valuable hard, medium and soft woods of Guyana, using the properties and qualities to full effect. “Bash” represents “a party of birds” seen along the Lethem road where they gather; the imposing “Bush Hunter” uses the hard centre of the rare leopard wood; the wood of the hardy Kaiambe savannah tree is used in several works, and also inspires a work about the birth of nearby horses who shelter under the tree; “Biswa” is another version of the mythical Shape Shifter, while “Cambana” depicts in soft corkwood the vulnerable butterfly in its chrysalis, and in contrast to many of his volumetric forms, “Cotton Dance” is an elegant, abstract play of lines.

We owe a debt of gratitude to the Amerindian artists of Guyana for their celebration and perpetuation of this heritage.

‘Silent Witness’ art exhibition continues until October 12, 2013, at Castellani House. (Guyana Times Sunday Magazine)