Part 1

It is not surprising that almost all of the sculptures in the National Collection are made out of wood, arising from the fact that accessibility to material is a necessary criterion for artists and no doubt wood sufficed in this heavily-forested land. It is also evident that sculptures in the National Collection predominantly emulate the human figure, ranging from the representational to the abstract in all manner of expression.

The oldest known Guyanese sculptor, Cedric Winter (1902-1974) is yet to be represented in the National Collection. The oldest-dated sculpture in the National Collection is “Spirit Guide” by the self- taught artist Philip Moore (1921-2012), referred to as the doyen of the Guyanese art world. This piece was carved in 1947, almost two decades after the first Guyanese art exhibition in 1929 during the colonial period. Moore, unlike many other artists, carved his niche from the onset, producing a body of work unmatched in the sculptural arena of Guyana. While infused with spiritual motivation and self-realization of his African ancestral homeland – a place where he never set foot – his sculpture embodies Guyanese mythology, folklore and creole culture.

The grand exhibition in 1931, organized by Barbadian artist living in Guyana, Goldie White, nurtured an art group- the British Guiana Arts & Craft Society (BGACS). The group comprised of locals and foreigners and staged annual Christmas art exhibitions. The group eventually gave birth to the Guianese Art Group (GAG) in 1944. Philip Moore was among those exhibiting with the BGACS in the latter 1940s.

The acclaimed “Father of Guyanese Art”, E. R. Burrowes, also of Barbadian heritage, left the BGACS and formed the Working Peoples Art Class (WPAC) in 1948 which existed for almost two decades until 1961. It was the first group of its kind that was structured in a way geared towards an art education process. During this time, the group members excelled, earning scholarships to Europe. It was this group that decided the future of Art in Guyana. While they were all painters, a few attempted sculpture, including E.R. Burrowes. Burrowes’ alabaster miniature sculpture “Pomona”, in the National Collection, is truly a treasure. Burrowes, after returning from his European scholarships pursuing studies in art, had developed his sculptural techniques to an extent that allowed him to execute large work such as the monument to the labour leader Hubert Nathaniel Critchlow, executed in 1964.

Two notable members from the WPAC, who earned scholarships, are Stanley Greaves and Denis Williams. Greaves, who majored in sculpture, on his return, pursued painting relentlessly to such a degree of unimaginable distinction that his sculpture almost became dormant. “Standing Figure”, also part of the National Collection, exemplifies the excellence which typifies both his sculptural and painterly work. Williams, who studied painting, later went on to broaden his area of studies when he pioneered the fields of archeology and anthropology in Guyana. Williams, however, continued the trend of art groupings when he founded the E.R. Burrowes School of Art in 1975, which still functions as a formal institution responsible for the output of outstanding sculptors.

The self-taught sculptor Campton Paris, like Philip Moore, also enjoyed participating in the exhibitions of the BGACS during the 1940s. His sculptures, in the National collection, exemplified by his relief series of Caribbean writers, tell clearly of the interest in representational imagery which prevailed during his time especially among painters. Abstract art was not an option for him.

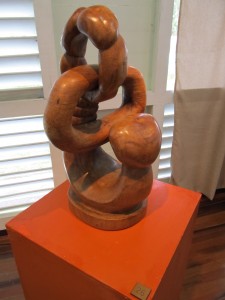

Parris gave way to Gary Thomas, who won numerous national awards including the first prize for sculpture in the recent Guyana Visual Arts Competition (2012). Self- taught under the guidance of Denis Williams, Thomas came onto the scene during the exciting period that began at the end of the 1960’s and saw Guyana becoming a republic and the birth of the Caribbean Festival of Arts (Carifesta) in 1972. Using the human form as the basis for distortion and variation combined with the technique of ‘holing’ and a smooth finish, Thomas was able to create dynamic compositions and movement in wood. Many of his titles, such as “Retrogression”, were never extraordinary or superficial but rather simple reflections from his secular life.

Among those influenced by Thomas is the remarkable Sealey family – father, four brothers, one sister and a brother-in-law of the third son Andrea Sealey. The largest known artist/sculpting family in Guyana, they are all completely self-taught except for the sister who went on to formal training at the Burrowes School of Art. Andrea Sealey’s fortunate state, patronage by the late President Desmond Hoyte, sees his piece “Untitled” (Figures in Motion) becoming a part of the National Collection.

Omowale Lumumba, a master of design in the neo-primitive style, worked alongside Gary Thomas. These artists seemed interested not in the perfect form but in the perfect distortion which penetrates through mere outward appearance to the essence. Simplification, narration, schematization and condensation are characteristics of their style and are frequently seen in the works of artists such as Ernest Van Dyke, Andrea Sealey and John Clowes, who came under their direct influence. Denis Williams referred to these sculptors as the “country boys” and dubbed them the “Village Movement”. Today, their style and technique echo in the work of artists like Ras lah and Marvin Phillips, who help to keep the movement alive on the Main Street avenue in Georgetown.

Winston Strick, artist of the era of Gary Thomas and Omawale Lumumba, studied Architectural Drafting and Fine Arts in the U.S. He worked in a style that stressed a kind of illusionism rather than mass. His subjects range from simple dignified genre and figure studies to landscapes, all with an emphasis on abstraction. One revelation is his assemblage “Woman”, a result of his constant striving for innovation and originality in working with leather in a direction away from functional craft to that of fine craft with sculptural principles.

The Burrowes School of Art was from the beginning based on the European model of formal training in the Visual Arts. In contrast to the earlier art groups and classes, this institution was integrated into the structured educational system of an independent country. With formal training in place, the output in sculpture became impeccable with such graduates as Ivor Thom, Colin Warde, Francis Ferreira and Winslow Craig, just to name a few.

Ivor Thom, whose carved wooden sculpture “Pregnant Woman” in the National Collection is comparable to his later achievements in bronze, returned from scholarship in Cuba after studying bronze casting. He has since received commissions for public monuments in bronze – all cast within these shores. (TO BE CONTINUED NEXT WEEK)