By Petamber Persaud

It will never be known how many arrows were left in the quiver of Stephanie Correia when she died in 2000. But those she utilised, Correia fired with unwavering accuracy, acquiring many trophies. In whatever field of human endeavour – teaching, pottery, poetry, painting or motherhood – she participated with distinction.

“Arrows from the Bow” was Correia’s first and only book of poems. Published in 1988, some 500 years after Columbus, this collection of poems may be the first of such book written in English by an indigenous woman writer. Significantly, the book was published by Red Thread, a Guyanese women’s network, to coincide with the historic retrospective exhibition ‘Sixty years of Women Artists in Guyana’ organised by the Guyana Women Artists’ Association.

The poems in this slim volume were like ‘arrows’ from a bow and were described by the author as “images playing hide-and-seek within my head”. Images of her father taking her to various indigenous reservations where she became acquainted with the rich folklore of her heritage; of her father teaching her to boat, fish and farm: “I followed him, small footsteps placed in his/and listened enchanted to his forest lore, secrets of bark and root and leaf and flower/I learned…to understand the laws of sustenance/a farmer’s patient waiting/and after dark he wove a spell with singing strings’ playing mari mari”.

Images of her father, Stephen Campbell, an Arawak from Santa Rosa on the Moruca Reservation who became the first indigenous legislator in the National Assembly of British Guiana, serving for nine years until his death in 1966.

Images of her mother, Umbelina, the daughter of Portuguese immigrants from Madeira, encouraging Stephanie and her siblings to sing harmonies together. Images of her mother with her beautiful voice passing on to them the deep feeling found in Portuguese fados. Images of Cabacaburi children dancing in the sun… finding a place in the sun.

Stephanie Helena Correia was born in April 1930 in Pomeroon, Essequibo, Guyana. She was the third of nine children. Her parents were Stephen and Umbelina Campbell. She attended Martindale R. C. Primary School and was only 14 when she was appointed pupil teacher at the same institution.

In 1950, she was called to the Teachers’ Training College in Georgetown. Two years later, she graduated as a Class 1 Trained Teacher. Correia won the Bain Gray Prize for the most outstanding student, placing first in both years at the college. It was at the college she came under the influence of the late E. R. Burrowes who was her tutor in art.

Her teaching career was short; shortened by marriage that frequently ruins the aspirations of many women. Fresh out of college, her first teaching assignment was at Sacred Heart R. C. Primary School in Main Street in 1953. For the next couple of years, she taught at St. Joseph, Mabaruma, North West District.

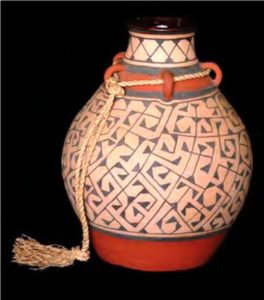

In her marriage to Vincent Jerome Correia in 1955, Guyana lost a teacher, but gained an artist, painter, ceramicist and anthropologist. The job of her husband, who was attached to the Interior Department, entailed frequent uprooting and resettling. It was during these trips that Correia started a database of sketches and notes on various nations of the region.

Marriage has its own blessings and frequently offspring become extensions of the parents, of the aspirations of the parents, a fulfilment of life. Stephanie and Vincent had eight children together, all of whom are involved in the fine arts, four becoming excellent potters.

In 1969, after the birth of her eighth child, she decided to revisit her artistic desire.

The decision was not easy for she had to balance her dedication to her family, her devotion to her art and fight for creative space, all against the backdrop of the indigenous woman in a somewhat unaccommodating mainstream male-dominated Guyanese society.

Except for short courses in Canada and U.S.A., Correia was virtually self-taught. She was like “that clay pot… ground, washed, blended, kneaded, moulded, carved, caressed, burnt… a battle-scarred warrior”!

In the poem, “A Part of Me”, she described her creations “a sculpture conceived in the mind and moulded permanently into form/a poem written down in the dawn after a sleepless night/a painting emerging stroke by stroke into a lasting statement”.

For her dedication to the arts and for creative use of indigenous materials and designs, she was awarded in 1980 a Medal of Service by the Government of Guyana. In 1996, she was again honoured by her country, this time with the Golden Arrow of Achievement (AA).

Before she died in 2000, Stephanie Helena Correia was researching the history of indigenous pottery in Guyana. It is hoped that the arrow in her quiver will hit the public soon for a nation ought not to diminish the import of its artistic heritage.

Responses to this author, call 592-226-0065 or by email: oraltradition2002@yahoo.com