Related posts

-

Linden man knifes woman and lover to death in jealous rage

A man is in Police custody after he reportedly stabbed his ex-lover and her new spouse... -

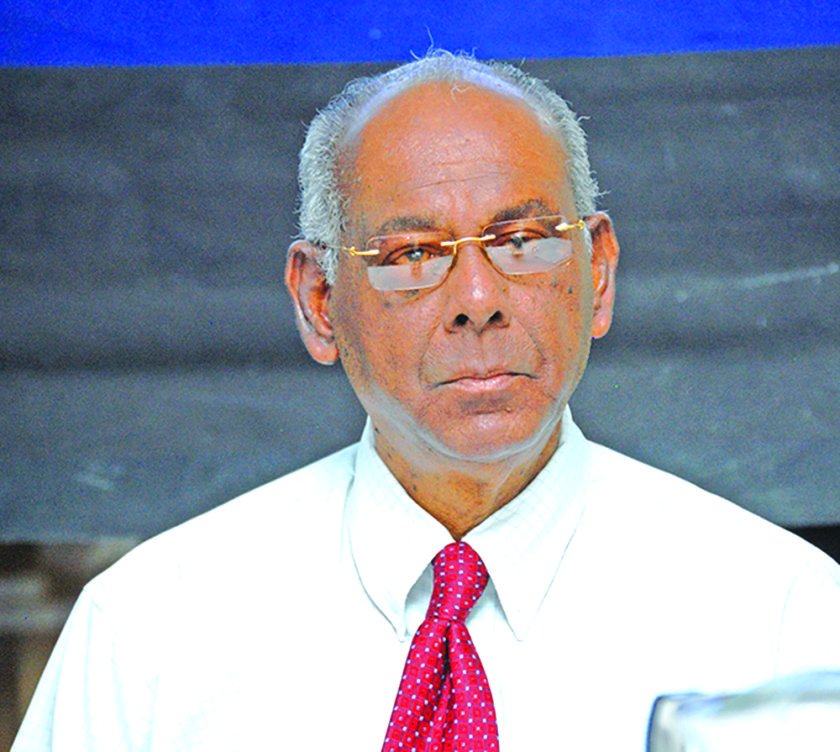

Ramkarran says GECOM’s 15-day deadline to announce results “not mandatory”

The 15-day deadline referenced in the Representation of the People Act, within which the Guyana Elections... -

Mottley says “there are forces that do not want to see votes recounted”

Chairperson of the Caribbean Community (Caricom), Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley, in a strongly-worded statement said...

Comments are closed.