Part 2

By Carl E. Hazlewood

It was the time of the summer of love in the United States and in Paris the student uprisings were being fomented; indeed, it seemed that everywhere music underscored youthful passions and obsessions. In the late 60s and early 70s, Guyana was certainly not exempted from aspects of this international youth revolution. In cosmopolitan Georgetown, Davson and a collection of young artists and intellectuals banded together to found a literary publication called ‘Expression’. This youthful multitalented avant-garde group showed abstract art, published poetry and fiction and argued through the nights about pertinent issues. Around this period, in addition to writing reviews for the local newspaper and showing art, 21-year-old Davson illustrated a book for children entitled, “How the Waraus Came” which retells an ancient Amerindian legend of how the first people populated the earth. In hindsight, it would appear that by this time he had already internalized the nuances and lore of the local as well as the conceptual rhythms of what he calls the “Caribbean sensation.”

However, before Victor Davson could produce his first mature body of work, he would have to survive the cultural turmoil and emotional dislocation caused by his decision to immigrate to the United States in 1973. The political situation in Guyana had become untenable for him at that point. In New York, he immediately received an artist-in-residence position at the Studio Museum in Harlem, although he still had to struggle through the typical depressive personal situations immigrants often face. Davson toiled in a variety of sub-menial positions while putting himself through school at Essex County College in Newark and the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where the strong academic skills he had acquired via a superb education in Guyana easily got him through to his college degree. Davson’s broad knowledge of art plus his acute skill as a draftsman, evident even as a teenager, are what continue to tie his various bodies of work together even when they appear on the surface to be completely different.

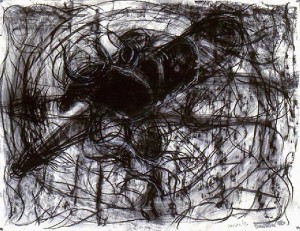

The first pieces to garner serious critical attention in his new American domicile were ‘Notational Works’, an extended series of large black works on heavy paper that straddle the line between drawing and painting. The carefully worked surfaces are structured with black and white lines and often barely perceptual proto-geometric shapes. At a glance, they seem quite reticent and reductivist in impulse, but on further observation one could see that the geometry of drawn forms and lines was felt— intuitive, rather than strictly Pythagorean. In the end, the varying densities of rubbed black pigments suggest folded fields of inflected darkness flattened into the lateral spaces of its support. It was one of these pieces that became Davson’s first work of art to enter an American museum collection. These totally abstract pigment-paintings are in a way the culmination of the artist’s investigation, began in Guyana, of contemporary modernist style and form.

The ensuing years have brought modifications to that severe-appearing method. Expressive colour has gradually reasserted itself on paper and canvas and in the latest paintings has effloresced into brilliant conceptual evocations of the Guyana masquerade. Of course, Davson has always used line to full effect, as seen in the delicate portraits of children drawn when he lived in Guyana. The ‘Limbo-Anancy’ series inspired by Guyana-born writer Wilson Harris’ literary metaphor employs a webbed vortex of line spun into a metaphorical web that is a poignant and symbolic attempt to reconnect long lost histories, peoples and experience, leaning back across the wide divide of time and place.