(Reprinted from Inter Press Service)

Georgetown, Guyana – Recent huge offshore oil discoveries are believed to have set Guyana– one of the poorest countries in South America–on a path to riches. But they have also highlighted the country’s development challenges and the potential impact of an oil boom.

Oil giant ExxonMobil has, over the last three years, drilled eight gushing discovery wells offshore with the potential to generate nearly USD20 billion in oil revenue annually by the end of the next decade.

“For Guyana where the current oil sector is located offshore, the direct environmental risks are primarily associated with oil spills, but will also include emissions from the operations, and from seismic activities that can affect marine species,” Dr David Singh, executive director of Conservation International Guyana, told IPS.

“The environmental risk increases with the number of oil wells in any one area.”

Singh said increasing environmental risks require increasing capacity to understand and manage these risks.

From a regulatory standpoint, he said this means building the institutional capacity in step with the development of the industry.

“For civil society, the responsibility is ours to learn about the industry, to contribute to the creation of good policies and laws related to the industry, and to ensure the highest levels of accountability from the industry and from the state towards the environment,” he said.

“It also requires us to support companies and initiatives that are in the business of clean, renewable energy generation, and in supporting efforts to reduce our ecological footprint. Even as we focus on these efforts we are cognisant of the limited human and institutional capacity of the country which will have an impact on the design and application of good and responsible environmental and social safeguards.”

Several commentators have observed that senior government officials here have little experience regulating a big oil industry or negotiating with international companies.

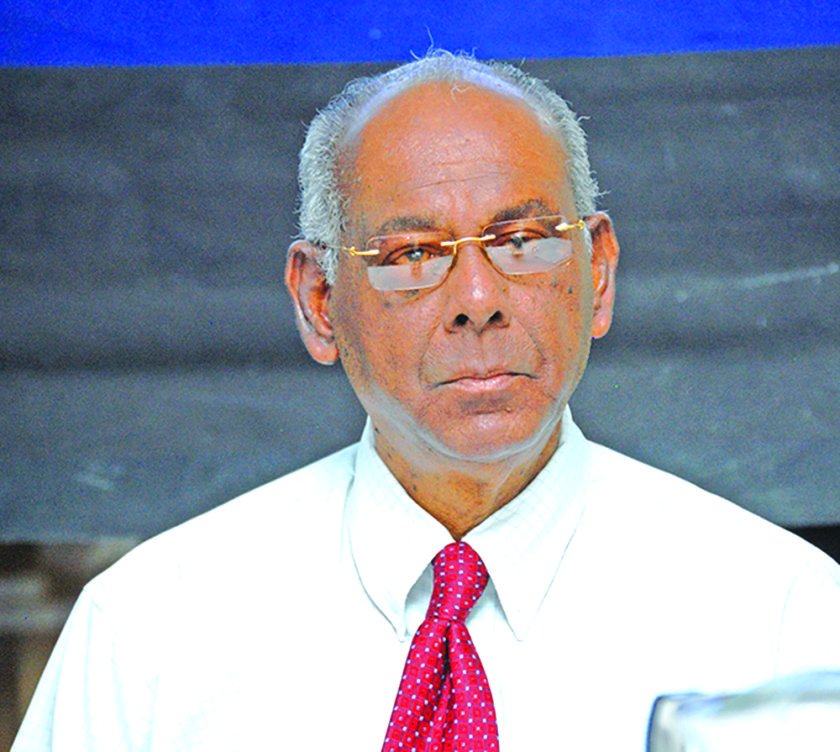

But Minister of Natural Resources Raphael Trotman said Guyana is prepared and has been building and strengthening its capacity to deal with the potential hazards that come with the development of an oil and gas sector.

He said no effort will be spared to ensure that Guyana puts a sound disaster risk reduction and management system in place so that it is prepared to prevent an oil spill or respond effectively should there be an accident in that regard.

“These are the jeopardies and these are the perils that we have to prepare for. We should not take them for granted or believe that we are dealing with something that is so far removed from our consciousness or our reality that we don’t have to be prepared,” Trotman told a national consultation on the drafting of the National Oil Spill Response Contingency Plan at the Civil Defence Commission’s.

“It has to be taken seriously and whilst the industry standards are very high, we do have a risk. We recognise that there is a risk. However, Government is making every effort to prepare for that risk. We expect that in 24 months when we go to production in the first quarter of 2020, we will meet not only minimum standards expected, but we will go past that and dare to say to ourselves and particularly to the world that we are ready for any eventuality,” he said.

Meanwhile, Tyrone Hall, a PhD Candidate at York University, is urging those involved in civil society in Guyana, especially its environmental sector, to assess the exemplary efforts underway in Belize.

Hall, who has been studying the issue, notes Belize recently found itself at the centre of rare positive environmental news of global importance.

Its portion of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, arguably the world’s longest living barrier reef and certainly this region’s most iconic marine asset, was removed from the World Heritage Sites’ endangered category after nearly a decade (mid-2009 to June 2018), according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation World Heritage Centre.

The decision was taken after Belize ditched plans to rapidly expand its nascent oil industry.

“There are lesson we can draw from the Belizean experience for raising the bar and boldly re-imagining environmental responses in the face of a petro-economic reorientation,” Hall said.

“In other words, while oil exploration is unlikely to be halted in Guyana at this point, the environmental community, and broader civil society must not settle into vassal like, aid-recipient disposition.

“It should raise its expectations, and also challenge, contextualise and transcend the singularly economistic conventions being drawn from distance places,” Hall added.

ExxonMobil has made eight discoveries in Guyana’s waters to date.

Production is expected to commence in the first quarter of 2020 with an estimated 120,000 barrels per day. This should increase to 220,000 barrels per day by 2022.

“What the oil revenues will allow us to do is to fulfil these dreams of the Guyanese people and to ensure that the quality of life for every citizen dramatically improves over a period of a few short years,” Trotman said.