By Dr Vishnu Bisram

By Dr Vishnu Bisram

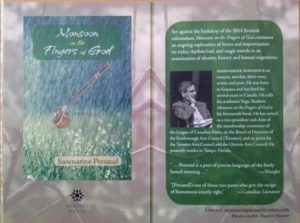

Monsoon on the Fingers of God, written by a Guyanese residing in America, is a thoughtful collection of poems relevant to Guyanese and other Caribbean people, the Indian sub-continent, and the UK. This collection of poems revolves around several topics, issues, and places. The collection is laden with a lifetime of experience and a finely honed craft, which the poet Sasenarine Persaud of East Coast brings to bear with full force on his writings.

Sasenarine is an essayist, novelist, short story writer, and poet. He was born in Guyana, and lived in Canada and Florida. This is his fourteenth book. He has a long history in writing and in poetry. He served as Vice President and Chair of the membership committee of the League of Canadian Poets, on the Board of Directors of the Scarborough Arts Council (Toronto), and on juries for the Toronto Arts Council and the Ontario Arts Council.

The title poem, “Monsoon on the Fingers of God” is a tribute to the great sitar maestro, Ravi Shankar and his historic and electrifying appearances at Monterey and Woodstock. This poem places the focus on Shankar’s genius as a musician and what he meant for American and world music, rather than the contemporary penchant on scandals that dominate news. Several poems deal with matters pertaining to the United Kingdom in which references are made to Scotland, England, Wales, and Ireland and other parts of the former British Empire, including India. Indeed, Scotland and the UK are touchstones for this collection but mention is made of so many other places. The poetry encourages an engagement with historical events, challenges, joys, emotions, and fears. Some of the subjects are on parents and children, historical events like slavery and indenture, and joyful memories of nature and sports as well as issues of faith. There is a consistent tone of introspection, grief, exploitation, abuse, and of overcoming hardship (like slavery, indentureship, migration, settling in a new strange place, etc.). The topics are effectively and skillfully addressed. Sasenarine Persaud writes with eloquence, rhythm and musicality evident from the first page.

Several poems deal with matters pertaining to the United Kingdom in which references are made to Scotland, England, Wales, and Ireland and other parts of the former British Empire, including India. Indeed, Scotland and the UK are touchstones for this collection but mention is made of so many other places. The poetry encourages an engagement with historical events, challenges, joys, emotions, and fears. Some of the subjects are on parents and children, historical events like slavery and indenture, and joyful memories of nature and sports as well as issues of faith. There is a consistent tone of introspection, grief, exploitation, abuse, and of overcoming hardship (like slavery, indentureship, migration, settling in a new strange place, etc.). The topics are effectively and skillfully addressed. Sasenarine Persaud writes with eloquence, rhythm and musicality evident from the first page.

In Scotland and the UK just prior to the 2014 Scottish referendum to separate from the UK and to affirm their identity and language, the author poet comes face to face with his own angst regarding identity and language – namely, his community’s migration from India and its 180 years presence in the Americas. He reflects on his Indian ancestors more dramatically so when he comes upon a Roma (Gypsy) beggar in the heart of Edinburgh, who is a splitting image of his great-grand mother, “Nani” (“Roma in Edinburgh”). But why be surprised? India is all around, in the numerals on street signs, in the language of yoga, and the Roma themselves, who are after all a people of Indian origin, discriminated in Europe for centuries because of their dark skin and their Indian language, Romani: “How could you/ make this trek from Rajasthan or UP? How could I? he rhetorically asked.

Except in a language we share with the world – yogayogayoga – through Anglo-Saxon cousins/ Sanskrit; or these numbers on streets and hotels/ storefront markers, Hindu Numerals/ Arabs borrowed from India – zero-invented…” The poem concludes questioning a multiple faceted identity: “…how do you compute/ British-Guianese-Guyanese-Canadian-American-Indian”.

The book presents his unique and inimitable poetry and word usage. Sasenarine opens the book with a couple of short poems followed by longer ones and then shorter ones. It is an effective mix on varied subjects (children, memory, karma, Scotland, etc.) written with different styles with well-chosen words. Sasenarine is a poet armed with a lot of knowledge and experience in his craft. And this book is a thoughtful and deep meditation on identity and migrations. Almost all the poems are relatively short – less than a page or a maximum two pages – except a couple that are quite long.

There are poems with obvious lyrical rhythms (“Approaching Day’s End”) and others that are simple free-verse structures as in “Master Batsman” and “Tiger Tiger” both tributes to iconic cricketer Shivnarine Chanderpaul. What he says of Chanderpaul, likened to the grace of the Bengal tiger is equally true of his own writing: “Do not be fooled by a cat’s easy gait/ heading for water at dusk, or dinner, bat’s repast another century, where glasses are tinted/ and made of Lord’s sand, where it is acceptable/ to mistake tiger for crab and diamond for dishwasher.” If a master batsman makes batting seem easy and effortless, so too the master poet. But don’t be fooled by that “easy gait” which has come from diligent commitment, practice and dedication to craft.

There is lyrical poetry in personal emotions and feelings from the poet though out this collection such as in “Sugar and Tea”, and elegant strophes (stanzas of varying line-length), as in the poem, “To a Kashmiri Child in a Hindu Refugee Camp in Delhi”.

Each poem is on a different scene, subject, thought, and realization, and occasionally, what appears to be carefully wrought prose rather than rhymes or rhythms in stanzas or verses. Each poem is a self-contained narrative or description; almost each is short. The book itself is divided into two sections.

The poems are written in free verse, sometimes with rhyming couplets; in whatever style, the work demonstrates mastery of several poetic forms and techniques. There are metaphors and allusions and an occasional epigraph. Use of alliteration and extended metaphors are skillfully used. Poetic language is concrete and evocative, with memorable lines or phrases like “—My bonnie lies over the ocean. My bonnie lies over the seas—in sun/ tomorrow we will again trawl ocean” in the poem titled “Fisherman Returning”. The several devices used by poets are integral to poetry writings and Sasenarine uses them effectively in this collection.

The poems rely more on content than on style. The poems are not written in any overt complex style, which is appealing. There are lyrical rhythms and clean free-verse structures. The language is deceptively simple as in the lines in the poem numbered “15”: “I cannot/ name the village from which my father’s father’s/ father’s father’s father came. And still, I do not/ envy you – grass eyes – and yet we have love/ a language we cannot give love until we love”.

Several of the poems were written to remind readers of specific messages or subjects as in those titled: “Roma in Edinburgh”,” Karma Mornings”, “Head Cover”, “A Sheep’s Life”, “The Scott Monument”, “Referendum”, “Searching for El Dorado”, “Sugar and Tea”, “Burial Grounds”, “Fisherman Returning” etc. Each poem captures the emotions of historic events (like indentureship, searching for gold in colonial times, burial, massacre in Sri Lanka, voting, etc.) in a way that makes the descriptions both personal (like the writer experienced them) and universal (history of so many colonial societies).

Readers get to understand history, politics, and religion, and the poems deepen the readers’ view of the subjects. The thoughts and insights in the poems are that of a very perceptive, educated, and skilled writer who knows his subjects and who seems to have spent a significant amount of time perfecting his writing. No doubt, this work is a voice of tranquility and unmistakable originality. The writer is applauded for the extraordinary collection of poems that demonstrate “Monsoon on the Fingers of God”.