Guyana became an independent nation in 1966, but its artists had already, from a generation before, begun to show independence of thought, action and vision. The artistic ferment in Georgetown in the decades between 1930 and 1960 is a yet largely-unrecognised intellectual and philosophical development in Guyana. The early part of this period laid the foundation for an art which lacks nothing in richness, complexity and ideation.

Samuel Horace Broodhagen (1883-1950) is identified as the earliest-known local artist. He was a painter of landscapes and portraits, but not much is known about his work. So was Cedric Winter (1902-1974), a sculptor, who created the altar screen for St James-the-Less Church in 1945. But the first decades of the 20th century were lean years for art in Guyana. One expatriate, Golde White, wrote to a friend that “[t]here has been no Art Exhibition for some time in this colony, and very little is done to encourage artistic talent”.

From the end of the 1920’s, White and other expatriates, along with the British Council, encouraged and supported the local men and women of talent. The colonials helped to found the British Guiana Arts and Crafts Society in 1931, and the British Council sponsored lectures and gave scholarships. This impetus produced our first formal artists such as Vivian Antrobus, R. G. Sharples, E.R. Burrowes, Reggie Phang and Sam Cummings.

On the other hand, Evelyn Williams argues that the colonial establishment “contextualised and controlled the models of cultural expression in the perpetuation of the systematic self-interest…imposing the imprints of a European consciousness”.

Here is where the pioneering local artists began asserting their independence: they soon broke away from the official influence, and began organising their own art groups and art classes. They formed the Guianese Art Group in 1945 and the Working People’s Art Class in 1948, which existed up to as late as 1961.

They attracted young people such as Denis Williams, Hubert Moshett, Marjorie Broodhagen, Enda Harte, Basil Hinds, and later on, Stanley Greaves, Ron Savory, Aubrey Williams, Donald Locke, Emerson Samuels and many others. The pioneers started a great line of artists who would take Guyana’s art into the next three decades and beyond.

On the surface, it seems that Guyanese art copies western art. But this is only superficially true. While our artists draw from the wide range of art approaches, styles and techniques, what they create is truly Guyanese. The pioneer artists broke away from the influence of the British School of landscape painting and used more investigative styles and techniques to delve into, rather than depict, Guyanese life.

They explored a broader range of themes and subjects. Apart from the landscape, they painted our people, pass-times and activities. Artists such as George Bowen (Jorge Bowen-Forbes), Alvin Bowman, Patrick Barrington, David Singh picked up this tradition from the pioneers and it continued in the works of Eddie Fredericks (our first indigenous painter), Basil and Angold Thompson, Cletus Henriques, Maylene Duncan, Winston Strick, Seunarine Munisar, Merlene Ellis, and a host of other artists right down to the present day.

Our art is a nationally-cohesive influence because of its democratic nature: it is not an elitist art; it takes an unprejudiced look at our life; it is a humanely-progressive art which propounds the richness and dignity of life. Even in the conflict-ridden 1960’s, Guyanese artists quietly asserted the common humanity, struggle, and worthiness of the Guyanese people through their landscapes and depictions of the life of the country in scenes of life and landscape.

In another discordant period, the 1990’s, artists such as Ohene Koama, Betsy Karim and Desmond Ali banded together as “The Guyana United Artists”; they and various other artists made a call through their many exhibitions for unity and peace. But our artists are not just parochial: they have responded to international conflicts such as the Gulf War, and champion international movements for global peace and liberation from oppression.

Our art is one of innate concern and responsibility. Right from the beginning, our artists showed a responsibility to the development of the nation through their social commentary. In 1961, Burrowes presciently offered his “Land of the Dolorous Guard” as a warning about developments in the country.

Stanley Greaves became famous for his “People of the Pavement” series in the 1950’s, and he continued his trenchant examination of our politics and culture in his “There’s a Meeting Here Tonight” (1990’s) and other artwork.

Just after the elation of independence, Cyril Kanhai’s sarcastic “Green Land of Guyana” pointed to the disjunction between political promises and reality. Bernadette Persaud bravely confronted authority with her “Gentleman in the Garden” series as economic and political pressures developed in the 1980’s.

From the 1990’s, Desmond Ali in his innovative, massive sculpture enlarged our thinking about Guyana’s political condition by expounding on the history of colonialism and the struggle for independence in the wider American region.

Our art gives Guyana root and substance: a hallmark of our art is how it draws from the well of our intrinsic cultures and experiences. By doing this, our artists give recognition to the inherence of the ancestral in the construction and existence of the Guyanese identity.

From the 1960’s, Stephanie Correia brought the forms and spirit of the first peoples of the country into formal art in her ceramic work. Eddie Fredericks depicted the rhythms of indigenous life; George Simon delved into his indigenous heritage to produce powerful art.

He also tutored Lokono artists – Oswald Hussein, Lynus Clenkien, Telford Taylor, Roland Taylor and others – who from the 1990’s revealed a hidden dimension of the Guyanese imagination with their shape-shifting works in wood. Philip Moore had, from the 1940’s, been intuitively drawing from his native African ancestry, but also recognising and utilising the iconography of the East Indian world-views.

Later, in the 1970’s, the Village Movement artists brought the African ancestry further into the limelight through the medium and style of their intuitive wood sculpture. Gary Thomas, Compton Parris, Omowale Lumumba, and Colin Warde were some of the main exponents of this movement, which still live on in the works of the Main Street Artists Brian Clarke, Ras Iah, Marvyn Phillips, Francis Ferreira and others.

In the 1980’s, Bernadette Persaud showed the power and relevance of East Indian religions and imagery in interpreting and understanding Guyana. Dudley Charles gave serious consideration to the beliefs of the folk, starting in the 1980’s with his “Old House” series and continuing this engagement in his subsequent works.

As in any other genuine art, in the particularity of Guyanese art, there is a connection to the universal. Aubrey William’s abstract paintings turn the Guyana landscape into the ground of examination of cosmic matters; Denis William’s Human World addresses all of modern industrial life; Philip Moore’s metaphysics apply to all; Winslow Craig’s themes touch universal chords.

Artists such as Terence Roberts, Carl Anderson and Derrick Callendar contemplate Guyana’s identity within the widest international context; Philbert Gajadhar celebrates East Indian ancestry, but also recognises its relatedness to other cultures as well, and so on. Our artists explore formal technical issues, tackle great questions of being, engage in metaphysics, comment on the world, and are alive to global efforts for freedom, justice, development and the best possibilities of human life.

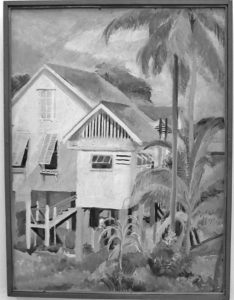

Notably, art will continue to lead, support and inspire our development.Presently at Castellani House, Vlissengen Road, an art exhibition, titled “In Retrospect”, by Jorge Bowen-Forbes is being held to celebrate the artist’s 80th birth anniversary as well as Guyana’s 51st independence anniversary.

It was opened on May 16, 2017 and will continue until June 3, 2017. Admission is free. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday to Friday and 2 to 6 p.m. on Saturday; the gallery is closed Sundays and holidays. (Artists’ information excerpted from notes by Alim Hosein)