by Petamber Persaud

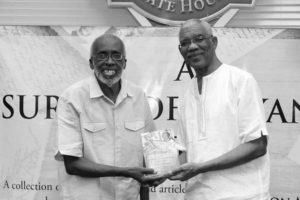

A Survey of Guyanese History is written from the perspective of one man, however, this does not diminish the extent, depth and validity of the work because the perspective of this one man encompasses an impressive and extensive array of research and writing, teaching and preaching experiences going all the way back to when Winston McGowan came into this world at a historic time during the early years of WWII, going on to attend the best schools –Sacred Heart Roman Catholic School and Queen’s College – in Georgetown, Guyana, stretching his imagination and his thirst for knowledge by entering the University College of the West Indies where he gained a Bachelor of Arts Degree with Special Honours, extending his search for answers to England where he secured a doctorate degree in West African History from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, and most importantly returning home to serve his country which he did (and continues to do even in retirement) with distinction by first joining the Department of History at the University of Guyana, serving in various capacities until he retired in August 2008 during which time plus a few more years wherein he occupied the Walter Rodney Chair in History for many years, crowned with the prestigious title Emeritus Professor, entrusted with the careers of emerging academics/historians as he served in the capacity of External Examiner for Doctoral dissertations at the University of Waterloo and as Examiner for the Caribbean Secondary Examination Certificate in History, honoured by his country with two national awards, the Arrow of Achievement (A.A.) and the Cacique Crown of Honour (C.C.H.), and launched his magna opus under the patronage of a sitting Head of State, President Granger – historian and man of letters.

Furthermore, according to historian Dr. James Rose writing the foreword of the book ‘[t]he process of historical writing involves investigation and analysis of competing ideas, facts and purported facts to create coherent narratives that explain “what happened” and “why or how it happened” and modern historical writing is not shy on drawing upon the social sciences… to explain historical events’.

The book runs into almost 500 pages, perhaps significant of the number of years since Columbus sojourned in this part of the New World that we are writing our own history. The number of pages matters to both the reader and the writer. For the reader, it may take quite a few sittings to weed through a few sections of the text. But for the writer, it had taken a number of years to put together; in fact, A Survey of Guyanese History, constitutes a life’s work, a man’s life’s work which ought to be afforded due regards and full respect in order to fulfil the expectation of the author that ‘this collection of essays will be of benefit not only to the general public, but also especially to teachers and students of Guyanese and Caribbean History. If that hope is realised, the collection will be a useful addition to the existing body of knowledge on this subject’. That number of pages is divided into eleven sections which are further subdivided into short essays and long papers of which many are ‘original works, many in areas previously unattended’ (James Rose), all designed for easier access, comprehension and appreciation, intent on the sharing of knowledge.

The quality of the work is even more impressive than its quantity evident in the first two essays of the book ‘Guyana, 200 years ago’ and ‘Guyana, 100 years ago’ which set the tone for the collection, evident in the acknowledgement of previous studies from which the author benefited but he gingerly pointed out that none of the essays is ‘merely a synthesis of previously available information’, evident in questioning previous text sometimes running counter to previous ‘facts’, evident in providing a very useful section to each essay labelled ‘For further reading’, evident in the extensive bibliography, a very handy index, and the use of primary source material especial in the essays on fishing, cricket and church history.

There are more than a hundred and one relevant uncovered gems to take away from this book but the reader is encouraged to polish those gems for his or her self.

The quality of the work is even more impressive than its quantity as the author in the first sentence of his preface declared that [t]his is not a General History of Guyana’ and in the following sentence lamented ‘the lack of an authoritative modern general text still remains a major deficiency in the growing historiography’ of Guyana, goading those change makers and those in authority to action.

(Copies are available from Guyenterprise and Austin’s)

Responses to this author please telephone 226-0065 of email: oraltradition2002@yahoo.com (Sunday Times Magazine)