British Guiana was the earliest and longest commercial producer of balata among the Guianas.According to “Tropical Forests of the Guiana Shield: Ancient Forests in a Modern World”, edited by D. S. Hammond, almost 28,000 t was produced between 1893 and 1988,though commercial production of balata ceased in 1982.

While indigenous populations had long used balata to make balls for playing games, temporary tooth fillings and for carving decorative art work such as figurines, the discovery of a“rubber tree” boosted the economic activity in British Guiana as worldwide demand for rubber intensified for machinery belting; to cover submarine telegraph cables, as well as for the newly invented motor industry.

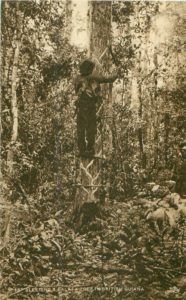

Balata is obtained from the latex of the South American tree manilkara bidentate, known popularly as the bulletwood tree. Balata is also known as wild rubber or natural latex. Incisions are made on the trees and the trees are then “bled” or “milked” for the sap. This is known as balata bleeding. The persons who carry out this activity are commonly called “balata bleeders”.

According to some accounts, early balata bleeding was carried out in Pomeroon in the North West District but this quickly declined as the trees were illicitly cut down rather than bled by incisions.

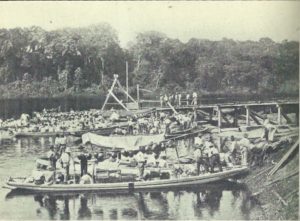

Most of the balata bleeding in Guyana took place in the foothills of the Kanuku Mountains in the Rupununi. It is estimated that nearly half of the indigenous male population of the Rupununi district was employed in balata bleeding by 1930.

Karanambu (Karanambo) in Rupununi, is said to have been founded as a balata gum collection station in 1927 by Edward “Tiny” McTurk.

A Mr D. Melville of Berbice, in his correspondence with the Royal Agricultural and Commercial Society of British Guiana, stated that in Berbice balata is found in abundance on the low, swampy reefs of Canje.

According to Melville’s correspondence, the Berbice “Bully – tree”, from which the gum was obtained, produces a greater amount of sap during the rainy season; the best time to “tap” for the milk was early morning or a day or two after the full moon.

From 1863 – 1865, balata shipments in Berbice amounted to just over 40,000 lbs.

At the peak of the industry’s earnings from 1890 – 1920, balata revenues accounted for some 80 per cent of total annual government forest product revenue between 1900 and 1925. After 1925, as world demand dropped, this was reduced to 43 per cent; by the 1950s it had amounted to just 2 -3 per cent.

As commercial wireless telegraphy and eventually phone services became widespread, demand for the rubber was curbed, leading to the beginning of the end of the rubber boom. By the 1950s, as synthetic rubber was developed cheaper than natural latex, natural rubber from golf balls to shoes was replaced and the rubber industry buckled.

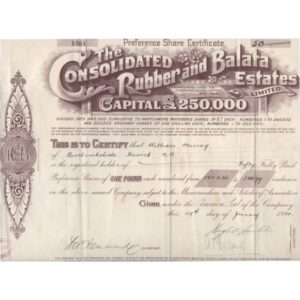

In British Guiana,by 1919, balata companies were already feeling the squeeze of the drastic depreciation of rubber prices. A.F. White, of Consolidated Rubber and Balata Estates Limited operating on the colony, once requested substantial assistance from the Crown to aid the industry.

However, in the London Gazette of July 1922 notice was published of an Extraordinary General Meeting of the Consolidated Rubber and Balata Estates Ltd. to be held for the purpose of officially liquidating the company which could not, “by reasons of its liabilities… continue its business…”

In “Tropical Forests of the Guiana Shield: Ancient Forests in a Modern World” it is noted that commercial bleeding of the balata tree led to some 900,000 to 4.8 million trees being killed across the major producing regions of the country during its 125-year-old history of balata production.

Preserving our heritage through pictures